Five lessons for participatory planning during a pandemic

Participatory planning pre-pandemic in Khorog, Tajikistan in 2018. AKAH looked at the experience of some leading urban planning practitioners in the developing world for lessons on how to continue community engagement during a pandemic.

AKDN

Despite mass lockdowns and social distancing measures imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, urban planners and designers have continued work to support vulnerable communities around the world. Beyond the immediate priority of ensuring everyone’s health, safety and livelihoods, the crisis is a time to rethink the way we plan, design, develop and manage our cities, and for designers to reconsider tools and techniques aimed at building the resilience of communities in need.

So, how have designers continued to engage with communities? How have they improved their participatory planning tools? And what potential discoveries have they made?

The Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network, looked into the experience of some leading urban planning practitioners in the developing world to answer these questions and inform its own work during the pandemic. These practitioners include Rahul Srivastava, Cofounder of Urbz (India); Jacqueline Cuyler, Director and Cofounder of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement (South Africa); and Vera Bukachi and Regina Opondo of Kounkuey Design Initiative (Kenya).

To implement community workshops safely, 1to1 – Agency of Engagement employs wipeable surfaces for mapping.

Courtesy of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement

1. Use established tools when going remote

Like most businesses continuing with work while ensuring safe conditions, development practitioners went online – using and testing online platforms to communicate and run workshops. Although “there is no substitute for face-to-face interaction”, stated Rahul Sriviasta of Urbz, as we discussed his work in Dharavi, India, there has been great success running participatory workshops remotely.

After the first weeks of widespread remote working proved that internal and external communications were still operating, each of the organisations we spoke to were energised by the possibility offered by the many digital platforms available. They tested online survey forms, social media outlets, video conferencing programmes, smartphone to GIS mapping tools, and more. However, there was some resistance to adoption of new tools by the communities, and they discovered the most effective engagement tools were the ones communities were already using.

“We have found that existing platforms are the only way that people communicate because nobody wants to download a new app on their phone just to talk to us. … If it doesn't already exist, it's not going to happen,” said Jacqueline Cuyler of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement.

While it was proven that social messaging app groups were the best way of communicating, organising and maintaining critical engagement with residents, the following questions arose: Who has access to smartphones and data in these vulnerable communities? Are we reaching a broad audience?

Where Kounkuey Design Initiative would have previously provided food or care items at their community planning workshops prior to the COVID pandemic, it now offers data bundles. It estimates that 50 percent of the residents in Kibera have a smartphone and if they don’t, the initiative helps coordinate smartphone sharing.

“If anyone who we've identified doesn’t have a smartphone, we try and get them to someone who has a phone and also provide them a data bundle to participate,” said Vera Bukachi of Kounkuey Design Initiative.

2. Don’t underestimate low-tech safe solutions

While much of the work has gone online, each of the organisations we spoke with has continued to run face-to-face community workshops while employing necessary safety measures. 1to1 – Agency of Engagement summarised its lessons learnt when implementing community workshops safely:

Follow the latest WHO and local guidelines and provide the necessary equipment: face masks, hand sanitiser, hand washing facilities, etc

Remind participants of good COVID prevention and safety practices though posters and notice boards

Use wipeable surfaces and laminate everything, e.g., Use clear tablecloths over drawings or print drawings on vinyl for people to draw on, then sanitise.

1to1 – Agency of Engagement uses plastic tablecloths that can be sanitised as an important safety measure.

Courtesy of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement

3. Smaller groups = more engagement

The reduced number of participants able to engage in a single workshop has been a major challenge for each organisation, whether this means splitting groups to less than 10 participants or having representative delegates from community groups. Reduced numbers means more workshops, more staff, more time running and collating the results and therefore more funding. Managing the protocols also requires more staff – where previously one member of staff ran a workshop, six facilitators are now required.

“We have been very open with our donors about the fact that this is going to take longer than we intended because longer time means more money,” said Vera Bukachi of Kounkuey Design Initiative.

Speaking on how this has impacted the quality of resident participation, Jacqueline Cuyler explains that although the numbers of participants has reduced overall, the ability of each participant to contribute constructively has increased.

“The information and participation are much richer due to a lot more voices being clearly heard. Those loud voices in the room aren't drowning out the rest because we're in groups of only five or 10 instead of that one voice speaking over all 50. The other contributors now have the opportunity for airtime and have their own space to present an approach, a design, or a proposal,” said Jacqueline Cuyler of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement.

4. Data collection is essential to citizen safety

Rapidly collecting meaningful information and accurate data is one of the key aims of participatory planning. When working with vulnerable communities, development practitioners are best placed to access this accurate data and use it to raise awareness of activities or problems and challenge the COVID response. This is what Kounkuey Design Initiative and 1to1 – Agency of Engagement have done.

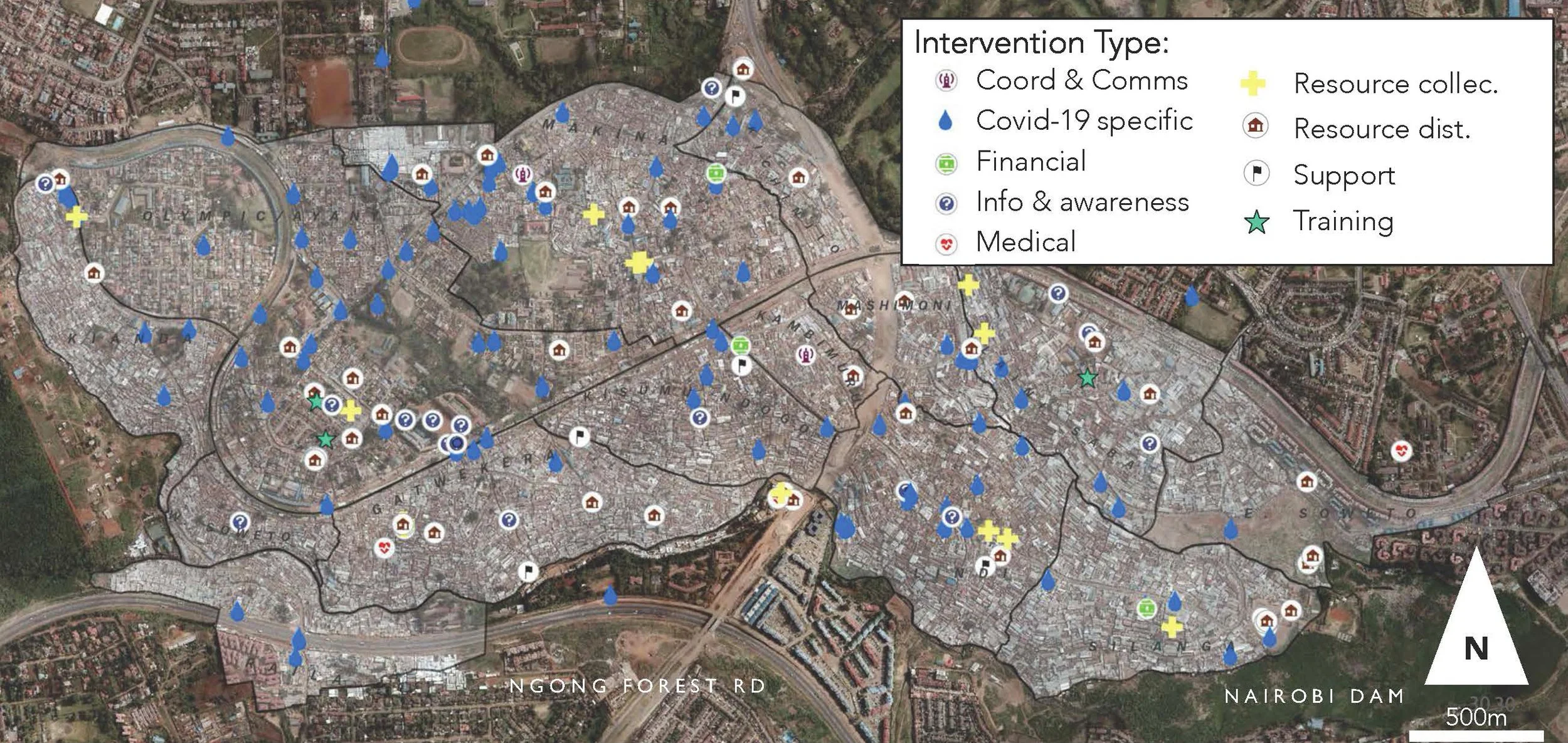

Kounkuey Design Initiative has been working with Kings College London to map activities in Kibera during the COVID pandemic.

Kounkuey Design Initiative’s GIS mapping of community initiated COVID-19 responses.

Courtesy of Kounkuey Design Initiative

“It's everything from providing water to educational materials, because schools were closed, and from providing clothing to sanitary materials for women who can't afford them, all projects established just as a result of COVID,” said Vera Bukachi of Kounkuey Design Initiative.

Amongst the many discoveries found was that it was a 9-minute round trip to/from dedicated hand washing stations for 80 percent of residents, longer for the other 20 percent. To combat this and the other problems discussed above over 270 interventions were recorded, with 105 of these locally led. This data advocates for a shift away from seeing informal settlements as “hotspots” of disease and more as leading the fight for solutions.

Similarly, 1to1 – Agency of Engagement has been mapping hand washing and toilet facilities in informal settlements in Johannesburg in order to advocate for more support and question whether lockdown rules apply to the same degree here. “How can you expect anyone to stay at home when their toilet is not even in their house?” said Jacqueline Cuyler of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement.

Responding to emergencies is a concerted effort, where communication and knowledge sharing becomes key to ensure citizen safety.

5. Trust is key

An existing presence in the community and established trust were essential for these organisations to achieve what they did amidst the current circumstances. However, these organisations also experienced a slowing of engagement during the pandemic with residents not responding to continued digital messaging without face-to-face interactions. “We have burnt years of social capital trying to maintain relationships over social media,” said Jacqueline Cuyler of 1to1 – Agency of Engagement.

There are still clear gaps in remote working and engaging with communities when social distancing and wearing a mask is required. As Vera Bukachi of Kounkuey Design Initiative highlighted, 80 percent of communication is body language, which is not expressed over video calls and conflict resolution is much easier face-to-face. Therefore, a balance between online and face-to-face interactions is needed.

“We have realised that if we are not able to do 100 percent face-to-face, we can still be effective and efficient. We are in the process of finding that balance. So, going forward, providing that COVID-19 is in decline, we will go back to more physical meetings, but there will be less than we used to have because they aren’t as necessary,” said Regina Opondo of Kounkuey Design Initiative.

The experiences of these practitioners reinforce the need for flexibility and persistence in the face of uncertain conditions. Looking at these approaches the COVID19 pandemic has clearly created an important opportunity to reimagine how best to engage communities and support their voice and agency.

AKAH has created an urban and rural planning framework and participatory planning methodology (referred to as “Habitat Planning”) for village level, peri-urban and urban planning. AKAH is using the framework in four locations in Tajikistan and Afghanistan, and will soon launch similar projects across Pakistan, Syria and India. To further strengthen community engagement in Habitat Planning, AKAH will apply some of the lessons learnt from the experience of these practitioners during the COVID19 pandemic.

Currently, AKAH is working with the Government of Tajikistan and UN-Habitat on a Habitat Planning initiative – the Khorog Urban Resilience Programme (KURP) – to guide environmentally resilient and sustainable urban development and economic growth in the high-mountain settlement of Khorog. The initiative will provide technical support to national and municipal authorities to create a spatial strategic plan, guidelines and policies to guide the future urban growth of Khorog.